If, like me, you are someone who tends to avoid conflict, I have a suggestion for you: imagine the conflict as a rubber band with you holding one side of it and an antagonist holding the other side. We know that stretching a rubber band too far will cause it to snap and be of no use; but a loose rubber band isn’t very useful either. By avoiding and not engaging in conflict, the discourse becomes like a loose rubber band. However, stretching yourself a bit makes it much easier to bridge barriers and take steps towards joint action.

Photo credit: Brand New Images / Pixland / Getty Images

But how to create the conditions for a optimally stretched rubber band? A brilliant online course called Leaning into Conflict helped me understand my own approach to conflict as well as how to prepare for and actually engage in areas of disagreement. With increased understanding and tools to apply, my confidence has been boosted. Rather than avoiding difficult conversations, I’m excited by the potential of uncovering the real interests underlying a conflict and of transferring negative energies into a more constructive search for solutions. Indeed, being able to talk about our differences with respect is a definition of civility.

My own learning around conflict is still work in progress. To this end, here are three steps that work for me, though I strongly advise anyone working in multi-stakeholder situations to take the Leaning into Conflict on-line course yourself. (The next one will be held 2-30 April 2019. More info here.)

Step 1 – Know your own conflict style

Changing how you deal with conflict starts from within. Even if your role is the “neutral convenor”, you bring your own power and conflict dynamics into the discussion. I found the (free) “self-saboteurs” test to be very useful for this reflection. For example, “pleasers” who feel it’s better to avoid conflict may unwittingly allow the rubber band to become too loose in a heated discussion. On the contrary, someone who typically likes to fight in a conflict situation may deliberately or subconsciously stretch the rubber band to breaking point.

Knowing your conflict style, you can take steps to avoid being “triggered” in a conflict situation and instead engage constructively. Indeed, we are not at the mercy of our emotions, and have an opportunity between a stimulus and response to pause and reflect before engaging.

Step 2 – Understand what is driving a conflict

The next stage is to prepare ahead of an exchange on the issue and understand what is truly driving the conflicted aspects.

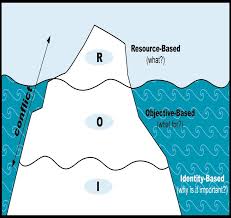

Jay Rothman (2014)

One of the course leaders shared an iceberg model (see image), which showed conflict over resources as typically the most visible aspect of any disagreement. However, often hiding below the surface of “who gets what money, time, etc.” is a lower layer of conflicting goals or objectives. Deeper still are fundamental issues around identities or personal values. This distinction is important to clarify not just for yourself, but also for the “other side” so that you are able to target the discussion around the “real” issues.

For example, I recently engaged with a colleague around a long-standing disagreement on a project. Before going into the meeting, I completed an “ARIA solo” exercise, reflecting on a first set of questions with the help of an ally:

- What do I blame the other side for in this conflict?

- Why is this issue so important to me? (thinking of the iceberg model)

- What did I contribute to the conflict? (being kind but honest with ourselves)

And then, importantly, the questions are repeated from the “other side’s” perspective:

- What might the other side blame me for in this disagreement?

- Why is this issue so important to them?

- What have they contributed to the conflict?

I found this exercise immensely helpful, not only to identify potential areas of mutual interest but also as it gave me more understanding, empathy and good will for the “other side”.

In this specific case, I had assumed previously that my colleague would like their staff time (i.e. resources) to be paid for in order to participate in the project. However, upon reflection – and validated in a later discussion – it became clear that the issue was more around different objectives and to a certain extent, different personal values in terms of what success looks like. Having this clarity before going into the meeting helped to avoid getting stuck addressing questions that weren’t important, and instead focus on identifying and reinforcing our shared goal as an aspect that could be built on.

Step 3 – Prepare to engage

In the past, when entering a discussion around a disagreement, I would feel under pressure to “win”; to “convince” the other side to align with me and agree on everything. It is reassuring to know now that the main objective is to create opportunities to truly hear the other side, what is important to them and why they care. Likewise, I need to be ready to be vulnerable, to express my needs and why I care.

I am now also better prepared in the event of being rejected during a discussion, having come across Jia’s Jang’s lessons from 100 days of rejection. When faced with a negative response, rather than fleeing, I aim to remain open and simply ask “why”. From there, different options can be brainstormed and next steps can be identified, further building trust and understanding.

Yes, it takes courage to engage. It also requires humility, recognising that the opposite of what you believe to be true may also be true from the perspective of the other person (see image below). This Danish MP’s inspiring story demonstrates her courage and humility in how she reached out and engaged with her online trolls over coffee in their homes.Ultimately, with enough preparation, you’re less likely to avoid conflict and instead choose to engage, and – by stretching the rubber band to its optimum tautness – you can reframe your relationships, making it easier to work together for the change you want to see.